The following blog is a chapter from this upcoming book, to honor winter solstice. With ease and comfort parked in a National Forest near Mt. Shasta, I shift my focus to review plant studies and Michaelmas for the upcoming biodynamic celebration.

Only vaguely familiar with the Michaelmas festival that takes place around the autumnal equinox and is incorporated into the celebration, I turn to several lectures from Steiner. I’m reminded of Steiner’s book The Cycle of The Earth As a Breathing Process of The Earth, read about a decade ago while struggling with seasonal affective disorder. Steiner’s words had completely relieved that angsty state. Steiner describes winter solstice as the still-point, as the very end of the inbreath of earth taking in its soul and spirit entirely below the earth’s surface. Then the stillpoint shifts and the outbreath begins, at first barely discernible. Spring equinox marks the midpoint of outbreath when daylight and darkness are equal; it is when soul and spirit of the earth further emerges out beyond the earth’s surface, when plant life begins to bud and be seen. This outward movement continues and culminates in summer solstice, the outbreath’s stillpoint on the longest day of the year, when all the earth’s soul and spirit is above-ground, floating about and communing with the vast outer cosmos. Then the earth’s inbreath begins once more, at first, once more, barely perceptible. Through summer during the first half of the inbreath, life and growth still proceed above the earth’s surface. Michaelmas occurs at the autumnal equinox, when the hours of light and dark are equal. It represents the end of active summer growth above ground that has waned and now ends, the harvest now complete and stored away for nourishment during this fallow time, as the inbreath of earth continues. The elemental spirits of all of nature also make their descent to beneath the ground, and prepare to rest as well as nourish this inner, still earth. Seeds beneath ground are in a barely perceptible gestation during this time. My personal sense of light and dark used to be most strongly focused on the light of summer solstice, also my birthday. That day was a natural high, a sense of levity, of being “out there.” Perhaps I was more susceptible to the darkness because of this birth-day. My former winter-solstice dread began at autumnal equinox when the earth’s cycle shifted to more darkness than light and was experienced as a crushing heaviness and sense of clinging by my nails to a crumbling cliff. This dread increased daily until the the winter solstice moment passed. Instantly, as though my feet discovered a ledge on the cliff to perch on, I could finally take an easy breath—like I made it through another year without plunging into the void. My “seasonal affective disorder” became most pronounced the third year of medical school. That was when I succumbed to the lack of spirit in my medical training—when my belief in holistic healing and the power of, for example, a natural childbirth, could not withstand the medical system. I consciously chose to play the long game, to become licensed and then hopefully integrate the medicine I longed to practice with conventional medicine. But by choosing to stay in this medical training, conventional medicine subsumed me. A part of me still hoped to remain a healer, yet the light of life dimmed; this formerly beloved and known light was now barely glimpsed in tiny pinpricks through the thick darkness. The lectures in The Cycle of the Earth released me from this winter solstice dread. They also helped me discern between the darkness of destructive forces and the dark of winter solstice. Instantaneously, I began to look forward to the increasing darkness that became moments of deepening stillness and quiet to sense the inner warmth and light of my own spirit that gathers inside of me like those plant seeds buried beneath the earth. I became conscious of the actual solstice moment when the inbreath pauses, that still-point—and experience it as an ever-slight twinge, like a faint earthquake or rocking of the earth that marks the outbreath’s beginning. This current “study” of the Archangel Michael and Michaelmas is now illuminated by my own experience of the earth’s inbreath. Michael represents this opportunity to gather our inner forces just as the earth takes in its soul and spirit. These dark hours provide time and space to prepare, nourish, and grow the inner light that shines regardless of any dark forces that surround me. The earth’s breathing, the polarity between dark and light, and this inner deep, quiet joy of winter balanced with summer’s expansive dance—Michael is in the center of all that. When Michaelmas occurs, as plant life grows fallow, Michael is there to remind us human beings of this opportunity to become internally and consciously active in the dark stillness. Though I barely registered this Michael-being when my seasonal affective disorder first lifted, now I recognize him as an essential spirit-guide; he is essential in my Joan-quest. My will to make the world a better place, my battles for goodness discovered through Joan are what Michaelmas is about. I don’t yet know much about why the art depicting Michael show him standing triumphantly on a demon or dragon during his descent underground. Does this represent how we all face our demons as the dark nights approach, how we must grapple with them during the descent? Is this symbolism akin to my discernment of dark destructive forces and the inner beauty of the dark times for creating inner light? Does the Archangel Michael hold our world in balance, hold the greatest enemies at bay to give us each the chance to fight for goodness until the spring, when the world once more emerges above-ground? In Twain’s book about Joan of Arc, yes, the Archangel Michael made an impression—he was her most important spirit guide to help her begin to fulfill her purpose; now, I realize Michael can also be my spirit guide. Perhaps it was his influence that enabled me to embrace winter solstice. Could it be Michael shows me and every human being we have the choice to find our courage and take up the challenge, embrace the darkness, and transmute it into goodness? Within this dark stillness, I glimpse a threshold that opens into multi-layered light; it is life after darkness—is the opposite of extinction. I have enough sense of Michael now to begin this next adventure. Mark Twain was my portal to Joan; I hope this upcoming celebration is my portal to Michael. Though eager to read more of Steiner’s lectures about Michael, I can take in only so much in a day. Besides, then there are the dishes. The fifth life process is maintenance. I will improve Jane’s daily maintenance by washing dishes more often, and shake out the small three-by-five-foot rug that holds all of my footsteps—no wonder it needs a shake every day! After cooking a meal that is much easier with clean dishes, I continue this break from enlightenment-study with some crafting. Since leaving the “Dylan Covered” CD with Joe, I’ve been trying to find it. Spotify does not include the raffle-ticket-won CD, but does include other covers—I’m especially enamored with Odetta singing Dylan. I had come across and downloaded a film, Rolling Thunder Review, a documentary about Bob Dylan’s ever-changing and enduring traveling band of that name, to further pursue this Dylan craze. While basting one of the mini-quilts started at Beth’s house in Vancouver, I watch this documentary, witness Dylan’s capacity to listen to others, build community, and nourish people and the earth as he brings music into the world for its own sake—simply because of its joy. Dylan joins my list of heroes, is a member of my personal troupe of warriors for the good. What a lovely additional gift from the Joe encounter—getting to know Dylan better. Funny how a small detail creates a thread woven through the tapestry of one’s biography, becoming a story in its own right. Like the song, “Simple Gifts,” that I wrote about in Re-Creation. Begun with bowing the tune by ear during those first months of playing Fiona, which led to a conversation with a Friend of the Shaker Community about the song’s origin that sparked my imagination and led to a Shaker library visit, then my questions still unanswered, finally led to a meeting with a Shaker community member who related the story about when “Simple Gifts” was written. Sometimes I tell this “Simple Gifts” story-thread at book readings, and then invite the audience to sing the song with me. The now-basted quilt put away and screen-time over, I settle into pre-bed reading—currently Peter Matthiessen’s book, Shadow Country. He mentions Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, throughout the book; in the context of his banker character who hopes that Twain will be his dinner guest with Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, other characters mention Clemens’ opinions and anecdotes about politics and current events, and in tonight’s chapter, his character, Mandy, expressed hope to someday see Twain with her own eyes—“that she might live long enough to behold her hero, if only from afar. . .” What a coincidence with my recent readings of Twain’s autobiographies, when I, too, wished I could behold him. I sought out Matthiesen’s book after recently re-reading The Snow Leopard, an impactful book from my youth. Matthiesen’s writing was so good, I decided to read everything else he wrote--Shadow Country is my first follow-through. The book takes place in the south during the mid-to-late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the same time period of Twain’s autobiographies. With his frequent reference to Twain, Matthiesen’s book is now interwoven into my interest in history of that era. My eyes pop wide with another coincidence. Twain wrote The Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc during the last part of the nineteenth century. Earlier today, Steiner described the Archangel Michael’s arrival to the earth sphere to fulfill his role as the prominent archangel of our time in the last third of the nineteenth century. What a coincidence. . . .The Archangel Michael arrives on earth and within months, after repeated unsuccessful attempts to write his Joan of Arc book, Twain succeeds, including his description of Joan’s visits with Michael. Images dance around me—the tantalizing influence Joan had throughout Twain’s life, the coincidental arrival of the Archangel Michael when he finally wrote The Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, the upcoming trip to San Miguel de Allende during the Michaelmas festival week, and my own Joan-quest. Dear Reader, Before I delve further into this topic of the Archangel Michael, I must confess. Perhaps you have already gleaned from my writing that I perceive a spiritual world and experience spirit everywhere, including minerals, machines, everywhere. Well-educated in the scientific world, my perceptions have always gone beyond science. I was as awed by electron microscopes as any other doctor or researcher, yet the vast spiritual realm was always present and beyond what a microscope could expose and explain. I learned about DNA, yet after the phenomenal achievement of “cracking the DNA code,” all the expected answers to how we exist and how to achieve health did not “materialize.” I love using that word in this context. Now that you have read the first two sections of this book, you may already be annoyed at my spiritual references. If that is the case, you may be more annoyed with this section. Some of my friends who are materialistic to the point of only believing truth in physical scientific research, blanch or argue or disregard me when I mention spiritual science. If that is the case, I invite us to agree to disagree. Consider this book fiction; on my copyright page disclaimer, I always state, memoir is fiction. I considered turning this Joan-quest into a book of fiction; one of Twain’s past lives was lived as Joan’s scribe, then Twain personally encounters the Archangel Michael during his most recent lifetime and that is the source of his passion about writing Joan of Arc, then a present-day protagonist discovers these connections and whoosh! starts a revolution to save the human race from extinction. But really, why bother with fiction? Truth is, indeed, stranger than fiction.

0 Comments

Hello Dear Readers, Below is a link to a five-minute video to introduce this distinction--infection or infectious disease or illness? If you want further information after watching, here is an additional link to begin your exploration. Blessings, warmth, joy, love,

Lynn Such a short hike today, up the Santa Elena Canyon, I didn’t even sweat; but I still have that crusty sensation on my skin from yesterday’s hike, because I’m in the desert—not many showers here.

Three nights ago, I set up a shower bag on the back door of my van named Jane; two nights ago, I had a sponge bath. Last night, I just wore baggy clothes to bed, as night and sleep came on quickly. Now, I want to immerse myself in water, possible at a boat launch and picnic area located on the banks of the Rio Grande, on the way back to the campground. A river guide pulling out canoes and loading them onto a trailer comments as I walk by him in my Crocks and suit, “There is good river access if you take the river trail—less muddy than here,” and he points to a rocky prominence down-river. I thank him, as this boat launch is quite steep, as well as muddy. I walk the short trail that soon opens onto a shallow and flat portion of the Rio Grande. Footprints cross a muddy slope toward water deep enough to immerse myself, and I walk in that direction. Suddenly, my left foot sinks in mud to above the knee, then the right foot sinks as I put weight on it, trying to pull out the other foot. I finally give up trying to also pull out the Crock sandal, and point my toes—my left foot slides out with a sucking sensation. I reach down to pull out the Crock—no way, it sinks further while trying to tug on it. My right leg snags on a mud-drowned stick, leaving a wide, harsh, red bruise as it emerges also, with a sucking sensation. As the left leg once more sinks, I flash on my sixth-grade report about how to get out of quicksand—position one’s body parallel to the surface. By now, my left arm is sunken, and I begin rearranging myself on hands and knees; three of my appendages are coated with thick, heavy mud as I crawl to solid, rocky ground. If I hadn’t realized this technique, I would have kept on sinking in this mud; I would have panicked. Back up on solid ground, I stand upright, and re-assess the terrain; by walking further downriver, I can stay on actual hard surfaces to get to a rocky part of the water flow. Fortunately, my feet are not completely tender, and this plan is feasible. In a shallow flow of water, I sit on small pebbles, and first rub off the mud—so sticky! Now I wish I’d covered my entire body with it—a true mud bath. Then I lie down for a whole-body rinse; good; this was what I had in mind. Jane is the only vehicle at the boat launch; the river guide is long-gone. I put out of my mind how if I’d called for help, none would have been available. This quick stop on the way back to the campground has become an adventure with a lost a pair of Crocks, and learning about mud that behaves like quicksand. Or is this mud a kind of quicksand? I’ll have to look that up when I have reception. . . On the way to the campground, I gaze in awe at the scenery—Big Bend National Park could define awe. I love this state of wonder; I love exploring, and immersion in solitude and nature. I don’t want to compromise this life. Yet I’ve just had one of those moments that was an in-my-face message about the risks of being alone on these explorations. About a month ago when hiking in an old-growth forest in Alabama, my toe tripped on a vine; I was walking too fast to catch myself, and landed with a full-body fall on a fortunately non-rocky trail. After the initial jar, I took a slow breath while lying still, assessing every body part; nothing was broken. The only real pain was in my left upper chest; I landed on the phone in my breast pocket, and I could feel a bruise, I hoped, and not a cracked upper rib. I soberly and carefully completed this walk. I was grateful that crawling out of that trail with a broken limb was not necessary; oh, yes, I was glad. Then, as today on the river, I was alone, and did not see another hiker the entire afternoon. The left upper chest pain lingered; I couldn’t take a deep breath, and considered getting an Xray, but then I knew they wouldn’t do anything about it if a rib was broken. A few more days later, I wondered if I had a lung injury—but didn’t worry enough to enter the medical system; the image of walking into a hospital or urgent care center is so averse, I’d have to really be injured. Over the following week, the pain slowly decreased; now, it’s barely present. I suspect I did crack a rib. From today’s mud adventure, the only consequences are the superficial injury from a sharp branch, and loss of a pair of plastic sandals. I’ve had them five years; now they are deep into the earth’s crust—made from petroleum products, I wonder, how many millennia will it take for them to turn back into liquid oil? Or is that transformation possible? A recent visit to a petroleum museum has stayed with me; I would return there if it was nearby, to see if I could answer that question. Those sandals were my only pair of slip-on shoes; I wore them when showering, and for quick trips to fill a water jug and such. They can be replaced in this world of consumption, for now. I imagine the ingenuity that may be required, perhaps in the near future, when such ample resources may instantly disappear, say, if Trump actually fired a nuclear missile and immediately all the boats filled with Chinese-made products headed to the U.S. turned back. . . .What then? How about a pair of carved wooden clogs, or moccasins made from animal hide? Or, remember those sandals made from old tires? Back to this life of personal risk that has definitely caught my attention with the fall, and almost getting sucked into a mud bank. I decide to take these reminders as a message to be ever more careful. And who is to say these risks are any less than commuting on a busy road in a large city? I don’t want to know the statistics. I also know I could be rationalizing. Still, deciding to be more careful and minimize the risks will serve me well. I could use a pair of walking sticks—add that to my shopping list: sandals, and walking sticks. I will also hone my senses ever more while assessing any situation; walk on hard ground in the desert when near water (now I really know that); make sure enough daylight remains to take a particular loop trail; pack extra water for a desert hike; give myself a free ticket to turn back on any trail, any time, if I sense disharmony in the environment for any reason, including within me—do I have the stamina and experience to pursue this particular adventure? This June, I will be sixty-six; I will build and maintain my strength so I can continue to live this life that I love. * * * Cruise control set at sixty miles an hour results in twenty-seven miles per gallon in my diesel-fueled van. I made this commitment to lower use of fossil fuel, and I save money. This van that I call Jane, is my home; so what if it takes another hour to get across Texas or Missouri? It’s one way to cope with this quandary of wanting to decrease oil consumption, yet my current lifestyle depends on using it. Interesting that most roads in Texas, where I’m currently driving southwest toward Big Bend National Park on the edge of Texas, has a seventy-five-mile-an-hour speed limit; their way of supporting oil production, by mandating a high speed limit in order to increase per capita consumption? I stick to my guns. Even on tertiary roads with a line of cars behind me, I stay at sixty miles an hour; when someone starts to pass, I slow down to accommodate their successful zoom ahead. The sparse, flat landscape dotted with oil pumps and refineries, the plume of flame that burns off the “offal,” provides a crude, poetic nature to this speed-limit musing. The name, Big Bend National Park, comes from the bend in the Rio Grande—from its southern flow to a western flow that defines the edge of Texas; the other side of the river is Mexico. I have heard others voice awe of its stunning landscape, and am driving an extra ten hours to get there; another fossil-fuel dilemma. Usually, I drive only an hour or two a day—I like road life, not driving. But this stark oil-production scenery does not invite lingering; I turn on a podcast to make driving another hour palatable. Zachary R. Wood, interviewed by Michael Ian Black on a podcast called, How to Be Amazing, is a young man whom I hope will be president of our country as soon as possible, I am that inspired by him. I will send him money to help with any campaign he is involved in, and am grateful for his presence on the planet. Much of his story is about how he engages in conversation with those he disagrees with; like a true democracy, right? His recent book is called, Uncensored: My Life and Uncomfortable Conversations at the Intersection of Black and White America. A sign for a Petroleum museum catches my eye; I take that exit. With Wood’s words fresh in my mind, here in the heart of Texas-oil-boom-land, he has inspired curiosity and determination; touring this museum is my version of a conversation with someone I disagree with. I vote; that’s about it for my political involvement; bureaucracy inspires a desire to shriek and leap out of my skin. Instead, my personal societal stance is captured by the phrase, “the personal is the political”; I am a child of the sixties, after all. How I spend my money, time, what I think and how I act—like driving at a lower speed, like being friendly, even when someone scowls at me, I strive to bring goodness into every moment and every encounter; these are my political statements. I walk into the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum, imbued with kindness, respect, compassion, and inner authority. The senior admission rate is eight dollars; hmm. I buy the ticket, pay money for this encounter—I’m on a mission. The phrase, Keep your friends close; keep your enemies closer, comes to mind. The first exhibit is a brief movie that debunks myths about the oil industry. I find out we’re not going to run out of oil—there is still plenty to serve our needs, far into the future. The geology, geography, and history exhibits answer some of my burning questions—I am indeed located in the heart of one of the world’s richest oil regions. Oil, still emerging from the ground at the rigs I’ve been driving by, began as organic life forms millions and millions of years ago. My favorite exhibited fossil is a Titanosaurus thigh bone—that’s what the sign says. I learn of the various layers of earth that cover these pools of organic black-gold substance, and how natural gas is one of those layers, and is considered the future of the oil industry, not having been as prolifically harvested, as yet. Sometimes oil simply lays on the ground—it has been found and used with such easy access for eons. Oil rigs also existed before this Texas oil boom, but when Ford’s assembly lines got going, the demand for gas to fuel those cars exponentially grew; exponentially might be an understatement; Texas’ oil history goes hand in hand with Ford’s car industry. Within a decade of the early nineteen-twenties, Texas’ oil boom literally erupted. Myriad paintings of that era are displayed in a large exhibit; most of the men look like John Wayne—as though working on an oil rig is a transformative activity, all of a sudden you are handsome. And all the women are beautiful. And then comes the painting of a romantic kiss. . . .Then a tense painting of a landsman—he is the one who puts together mineral rights deals—talking into the night with a ranch family, the two children fallen asleep at the table, the landsman faces personal financial ruin unless he can seal this deal, and does so with an offer to pay the family’s ranch taxes for this year. It’s a win-win situation—the successful oil drilling means everyone becomes rich beyond their imaginations! As I absorb this story of how Texas was a cattle-ranching culture that became an oil culture—almost overnight—I have clarity now how this region is completely dependent on oil for its economic survival. I think of all the big trucks I saw zooming in and out of the Walmart lot where I slept last night—their logos reflecting oil-related industry: refining, engineering, waste processing, welding, fracking—and most of the trucks were white; I wonder why they like their trucks white? The oil empire still dominates this region. If any of them knew I don’t drive over sixty miles an hour, would I have been safe last night? I’m old enough to remember stopping for gas, when the service included checking the oil level, tire pressures, and cleaning the windshield—by someone wearing a crisp and clean uniform. One of my favorite displays is of an old pump from that era, and beside it is a case with Wonder Bread(!), and a jug of milk. I remember eating Wonder Bread as a treat; we would mash up a slice with our fingers, roll it into a balls, then eat it that way—it tasted sort of like raw cookie dough. The nostalgia-display seems never-ending; the good old days, including stars like Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley: old Flying A commercials running on TV sets from the nineteen-fifties: and the cars—a huge room contains various versions of race cars, hammering home the connection between oil and car-love. Another exhibit displays other forms of power—wind, hydraulic, solar, nuclear—along with their respective percentages of productivity; in this museum, oil wins, hands down. My curiosity and openness has brought me this far through the museum, thank you, Zachary R. Woods; where I balk is at the entrance to an interactive exhibit in a tower—it looks like a Disney ride. I’m invited to take part in an exploration all over the world, for new oil sources; I would be locked into this event for over ten minutes. As the introductory spiel invites me to cross over the threshold before the sliding doors close for this group, I cannot step through; I suddenly feel nauseous, and walk back down the ramp. No, I cannot participate, even in my imagination. At the next exhibit, I’m introduced to all the various career options in the oil industry, and am invited to participate in a computer program to see which one would most suit me. Especially this exhibit evokes wonderment that I paid to see this. Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy comes to mind—her Church of PetrOleum, part of the third book; I wonder if she visited this museum as part of her research? The last exhibit is several rooms filled with semi-precious minerals—various quartzes, jade, you name it, as lovely as a sparkly display in any jewelry store. I sense they are part of the oil-production fairy tale, like all the John Wayne look-alikes, but how? What do these stupendous glittering and shining semi-precious minerals have to do with drilling for oil? They’re both created by enormous pressures under the earth’s surface. . .and when oil prospectors come knocking on the ranch owner’s door, the proposed agreement is for the various companies to hold oil, gas, and mineral rights—not just oil. . . That’s it. I walk out of the museum, with empathy for the state of Texas that has this history of winning the oil lottery over and over again; that really did happen in the early twentieth century, and it seemed too good to be true. Now to admit that maybe it is too good to be true, to give up the big win and embrace the reality that climate change really is happening in large part as a consequence of this bonanza, this boom, this economic heyday, seems inconceivable. No wonder the illusion that we can continue this oil industry indefinitely is so potent. But here is what I know about illusion; if I begin to see the falsehood for what it is, then new possibilities arrive through this truth. Creative ways for the oil industry to transform their resources into earth-saving measures could happen. The conversation has begun; from what I just learned at this museum, ongoing production of oil products is going to occur, no matter what. I am part of my culture, use petroleum products, including a fossil-fueled vehicle. I understand Texans’ and the world’s fierce ownership and identification with this industry, including these phenomenal fortunes that have been so easily acquired. I understand this desire to hang onto the illusion that scant damage is occurring on our earth. Illusion versus truth—oil barons and baronesses, please cherish our earth. Your children and grandchildren will have a better chance at the most viable life. As I climb back into Jane that is fueled by diesel, I wonder; what will it take for me to live without fossil fuel? I’m willing. My only regret is I did not take advantage of the museum curator’s offer to take a photo of me in one of the formula race cars—the only one of the exhibit that does not have an alarm going off if you touch it. She said, “Usually we have to help you get out of the car, it’s such a tight fit, but I think you could get out yourself.” I declined, at the time not wanting to associate myself with a race car. Now, I wish I did—I’d have a memento of this hopefully ongoing conversation with the oil barons, about our precious earth. Two-and-a-half years ago, my very first night living on the road, I pulled into a Walmart.

My van-dwelling friend Karl had told me about Walmarts--most of them are friendly to RVs and campers; because then, guess what? The overnighters go in and spend money. When he first told me, I scrunched my nose with distaste; I had never even been in one. I was loyal to my local hardware stores, clothing stores, and grocery stores, and associated Walmart with destroying small towns. That first night on the road, I had already used my free-overnight-RV parking app, and Walmart was the only option that popped up; few overnight options were available along that northernmost highway in New York--campgrounds already closed for the season, and I was averse to KOAs. Any port in a storm--in this case, relatively safe and quiet overnight parking. The app specified, go in to the store and request permission to park--this is a Walmart corporate policy, even when the store is known to be friendly to overnighters. I walked in, found customer service, and the friendly clerk responded, "Yes, park near the garden center, over that way," and she waved her arm to her right, my left. "Thank you," I said, smiling, and walked out. I parked my van named Jane in the designated area, turned off the engine, then sat in silence that was soon filled with a sense of thrill--I was launched, living my first night on the road--and who would have thought, this adventure would include Walmart. . . While setting up for dinner and bed, I fumbled a bit--where are the matches to light the Coleman stove? Oh, don't pull down the bed yet, I need to get the tea out of the storage bin for the morning. And, did I remember to pack salt? Where did I put my toothbrush? I managed to be in bed by eight-thirty, and slept soundly. Waking up in the morning, I asked myself, where am I? I'm in Jane, in a Walmart parking lot. I prefer campgrounds, surrounded by quiet and nature and dark nights. They're not always available, and often beyond my budget; I am retired, living on Social Security. Faced with the other choice of parking overnight at a truck stop with guaranteed semi-motors running through the night, I choose Walmarts. As Karl predicted, I began to shop there, too. They have the best price on propane canisters, and sometimes they are the only option for food. I am sad about this, knowing some family grocery store has bit the dust; what to do? Every time I walk into a Walmart, I have a bittersweet sense--especially when I walk into a friendly, clean Walmart, where the store greeter actually converses with me about local places to hike, or I witness several clerks chatting as though they really are happy to work there. I witness this burgeoning Walmart family making the best of this corporate entity that has steamrolled over small towns--and larger towns. When a Walmart is not that nice--kind of grungy, and the average weight of a customer is two-hundred-fifty pounds, and the clerks appear tired and depressed, that kind of ambiance diminishes the ease of overnight Walmart parking. I walked into one of those kinds of Walmarts, my app having listed it as okay to park overnight. But when I asked permission at customer service, the clerk called over the manager who frowned, and said, "No, we don't allow that anymore. Squatters refused to leave, said it was their right to stay as long as they wanted-- they had taken over our parking lot. So we changed our policy. You can't stay here." My heart fell. It was already past eight p.m., and the app listed no other nearby options. "Do you know of anywhere else I can park tonight? I'm kind of stranded." The manager turned away to put out another fire, and the clerk told me in a friendly voice, "If you go to the train station, you can park overnight there." He gave me directions, and I left. I'm familiar with entitlement of the wealthy; here is entitlement from someone living on the road, probably close to the bone. Entitlement in any social stratosphere hurts us all. I also wonder about the lack of health I just witnessed--the manager reeked of cigarettes and he had few teeth left, the clerk probably weighed over three hundred pounds, and how they turned me away--I was unwelcomed; that cannot be good for their own sense of well-being. In a way, I was glad to have been banished; I would not want to stay someplace so mistrustful, and the huge stacks of junk food at the entrance seemed to invite catastrophic illness. What if Walmart actually stopped selling any product whose first ingredient was sugar? The store would immediately be half-empty. As I walked toward Jane, I beamed as much goodness that I could muster, to all of us--so we will all turn the tide toward repair and growth and health and love. Sometimes I pull into a Walmart, and it's obviously okay to park there; an RV city has sprung up in one of the nether-reaches of the lot--shade awnings and picnic tables set up, once even a fellow working a portable table saw, people walking their dogs amongst the vans and RVs, eager to say hello to anyone willing to engage. I'm on the introvert-end of the spectrum, and park with my door faced away from the crowd, hoping for a quiet night. Last week, my laptop stopped working. I pretty much need a laptop for this writing life to continue. My smart phone still worked, and I looked up electronic or computer stores; on a Sunday afternoon, the only one open until the following morning was, you guessed it, Walmart. I walked in, for the first time, not for permission to park overnight, but only as a customer. In the electronics section--located always at the middle-back of the store, commonly near the on-line Pick-Up counter, and also where the second bathroom usually is (van-dwellers know where the bathrooms are, yes), I asked the friendly, youthful, carrot-topped fellow for help. He diagnosed that my plug-in port no longer worked; I needed an Apple store next, and he told me where the nearest one was located--an hour and a half away. I had become a real Walmart customer. Then again, I can take only so many Walmart parking lots. Glaring streetlights that block the sense of dawn approaching, early-morning delivery-truck sounds, knowing too well the layout of the stores, and the overwhelming displays of junk food, crowd my soul. Some van-dwellers stay at Walmarts all the time--I don't believe I'm capable. I strategize my budget to allow for more campgrounds when they are available, seek out national and state forests that offer dispersed camping, and often stay extra nights to refill my nature-tank. After two nights in a Missouri State Park and soaking up the quiet and forests and dark nights, I'm headed to the St. Louis area for several errands--to visit my "home" YMCA in Festus, the Mark Twain Museum in Hannibal, the Gateway Arch, and my van is due for an oil change. Time to dive back in to free overnight parking. After several Walmart-listings that haven't worked out, a Cracker Barrel parking option catches my eye--time to mix it up. I had a comfortable night at Cracker Barrel, thank you--including access to chicken-fried steak, and mug slogans such as, "You Go Girl! And Don't Come Back!" Hmm, one could take that a number of ways. But regarding St. Louis, the best-laid plan can have a life of its own. The weather forecast is scary--ice, wind, and record-breaking low temperatures, starting tomorrow night. Ice is one of my nemeses, and I do my utmost to avoid it. I decide to squeeze one destination in before high-tailing south to avoid the storm--the Mark Twain museum. Twain's book, The Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, has inspired me to seek information about Twain's personal history of how he wrote that book. I could write my own book about reading his book, and where it has led me--I've recently visited Rouen, France, to walk through the history of Saint Joan's trial and burning at the stake, for example. Twain's childhood home in Hannibal is a ways north of St. Louis; I rarely drive more than a few hours, but the desire to see this museum is enough to burn those extra miles. The drive takes longer than I'd hoped; by the time I arrive, the museum is open only one more hour. I buy the ticket anyway. The displays are mostly of Twain's boyhood home and neighborhood, and how they inspired his most well-known works such as Tom Sawyer. I appreciate those books, but nothing like the appreciation held for Joan. One museum-section provides a comprehensive time-line of Twain's life and accomplishments; I'm inspired to learn more, somehow. But not now; at four p.m. (winter closing hour), I start high-tailing it south; avoiding ice trumps even this Joan of Arc passion. I leave with some of what I'd hoped for. Of the two docents I spoke with, only one had heard of the Joan of Arc book, but she hadn't read it; that's interesting. Twain wrote a two-volume autobiography; I will read those, still hoping for more about his story of writing about Joan of Arc. And, standing in his childhood home was wonderful. Since the overnight parking app is often inaccurate, this time, I call ahead. Phones sometimes still work. Confirming I will be welcomed, I drive to a Walmart as far south as possible before the storm. I shop for several days' worth of food, including organic lemons and avocados. I am in a town with a large enough population to support a YMCA; Walmart is its only food-buying option. I surrender to this monopoly, and also gratefully refill my five-gallon water-jug for thirty-nine cents a gallon. The temperature is still in the forties; the storm is scheduled to arrive around midnight, starting with rain, then mixed precip, then by morning, snow and ice, with gusting winds. I did not get far enough southwest to avoid the ice--close, but not close enough. I settle in for the night, especially grateful for the furnace that runs off the diesel fuel, and plan to stay put right here in this friendly Walmart parking lot, until the roads are clear. It's hard to think about anything other than this weather; gusting winds over forty-five miles per hour, spitting snow and ice, windows iced over in some places a quarter of an inch, Jane rocking in the wind enough to spill my tea, furnace constantly running to keep the temperature close to sixty, temperatures falling through the day, with a predicted overnight low of thirteen degrees. I've become frozen along with the land. I use my tried-and-true gratitude list: I have a working furnace to generate heat; my phone works and I can call friends; I can write; I have plenty of food and water. How can I reframe this experience? I've begun describing my life as a semi-hermit living in a cave on wheels. I think of the Tibetan nun who lived in a Himalayan cave for seven years; I can go another day inside my cave on wheels. Here's the reframe; I'm on a retreat, inside of Jane, inside of my sacred cave. Then I wonder, how did she heat her cave? I'm going to research that. This reframing helps; I spend the day in various states of creativity--writing, painting, cooking, conversing on the phone with friends. About six in the evening after complete darkness has arrived, while preparing Jane for the night by covering the windows with insulation, the furnace overheats. I turn it off, then on, and it overheats again. Jane currently sits on a parking lot covered in ice that one could skate on. I've slept overnight in colder temperatures before, with a working furnace--but tonight, what am I going to do? I text my van-dweller friend, Karl; shall I use the Coleman stove set up on the floor as a heater, or keep Jane idling all night with her heater on? He texts back that running Jane is the safest, but to not go to sleep when the engine is running. Get Jane warmed up, heat water and fill containers to put in my bed, then sleep for as long as I'm warm, then repeat the process. Ouch. A motel is about a quarter mile away; but how would I walk to it? I have crampons, but the wind and cold and me walking through this desolation? If I stay in Jane, the worst-case scenario is I lose a night of sleep; I can live through that. I call my other brilliant how-to guy, Gary, and ask if it would be dangerous to try the furnace again. No, it isn't. It stays on without overheating when set at the lowest temperature, forty-eight degrees. I can "live" with that--I can sleep with that. I put on three thick layers, the one closest to my skin is a thick cashmere sweater--the word cashmere alone warms me up--and settle in. In the morning, I force myself out of the snug bed, and brew tea, as usual. While water is heating to a boil, I peel off the window insulation, and sun pours in--good; solar heat will help melt all the ice. The roads are still icy; I will not risk driving until the view out my window is of dry roads. Besides, it's now Sunday--even if I decided to brave the highway, places to repair the furnace won't be open until tomorrow morning. Back on top of the bed, nested in blankets, hats, fingerless gloves and sweaters, I give myself another pep talk, as I catch myself thinking unproductively, what if the furnace overheats again? I feel frozen again--not temperature-wise, but as though I cannot make the next move, whatever that is. I give myself a psychic shake; if it does, I'll deal with it--I already have the plan of running Jane for heat, and then sleeping as long as possible. Besides, tonight's low is predicted to be nineteen degrees, and wind is now mild--already easier. And, so far, so good; the furnace stays on at forty-eight degrees. More pep-talk: I lived in Scotland for a year, and recall most houses were heated in the winter to about fifty degrees--my frugal nature was at home in that country. Much of the world lives in this range of winter temperature; I'm uncomfortable, only. I'm spoiled with how warm I usually am. The frozen state dissipates, and I flow into this moment; I discover today's abundance through more creativity--writing, painting, playing the fiddle, and cooking. As I move, I generate more physical heat; as I create, I generate more heart heat. At the peak temperature of the day, I put on my crampons and walk toward the Walmart entrance. Closer to the building, the lot is dry, and I take off the crampons. Here is today's outing--a walk through Walmart to fill my two-gallon jug, and to buy some Hatch green chiles. I have a hankering for that kind of heat, too. Back at Jane, I open the side door to water the tree with my dishwater that has been sitting in a bucket on the side-door inner step--it has a film of ice on it. I'm starting to grasp microclimates within Jane--my bed is warm with body heat, by the door is freezing, sun beating directly in through a window is as good as a furnace. Monday morning, I wake up before six, and leave the window coverings on until the sun is up, so the furnace doesn't work so hard--it's still running, tolerating the forty-eight-degree setting, thank you. I drink tea and set my alarm for when Thermo-King opens, where I hope for repair. As light arrives, I pull back the insulated curtain to get into the freezing front cab, to start Jane and begin defrosting the windshield. I can't see yet through the layer of ice on the cab windows; when I remove the insulation from the back windows, I can see enough of the road to confirm that I will drive today. Good. After moving Jane off the adult-sized lego set used to level tires, my micro-climate education continues; on the side with solar radiation, the blocks are free and clear; on the other side, they're frozen into over an inch of ice. I get out my hammer to crack the ice and dislodge them, then toss the blocks onto the cab floor on the passenger side, set my GPS for Thermo-King where I am expected in an hour, and drive away from the true port in the storm that Walmart has been for three nights. Roger has just finished his description of a stroke he experienced three months ago, available in the previous blog. We converse in his tiny house that he uses for retreat, heated with a shoe-box-sized wood stove--a very peaceful and welcoming space.

I've said all this, and I'd love to hear your response to any or all of that. I always practiced medicine, and now I practice coaching, with the approach that all illnesses are opportunities to heal. Let me throw this out to you, then--all my life I had this terrible diet, and I never could go on a diet, I couldn't lose weight, I couldn't resist, I couldn't do this, I couldn't do that, and so the functional doctor told me all this--"You've got inflammation, you're pre-diabetic, you have markers for auto-immune illness," and she said, "lupus." And I said, I don't want lupus, and my initial reaction was, I want to die. My second reaction was, I'm going to do this (diet). And my third reaction was, I'll get over this, I can do this--all three in about thirty seconds. So those were my reactions that I think were very uncharacteristic from how I'd always been, up to that point. It's like I stepped into that healing. I think it's like that spin you've got, illness is a lack of healing, and it's finding that healing. I feel it's kind of like what I stepped into, for some reason. So then I was going around telling everybody, I can't do this, I can't eat that, and I joked, "I eat cardboard every day." And I told a friend who'd actually gone through something similar, and she told me, "You will not say, you can only eat cardboard, and your doctor won't let you eat this. You are going to say, I eat this way because I want to eat this way." My thirty-second reaction to that was, that was harsh. Thirty seconds after that I was, like, I want to step into that. And so that's become my approach, also--that I can do all this, it's my choice to do this, not because the doctor told me to do this. So that's where I got to where I am. Yes--the free-will "thing" is essential--that's part of my relief of not being in medicine any more, because people expected me to tell them what to do, and I never wanted to tell people what to do. Patients might hear that regardless, but it's always about our own decisions. If I tell someone to stop eating sugar, forget it. I've heard that a few times, it didn't mean anything to me. I'd stop sugar for the next ten minutes, and then I'd go right back. I tell people--I'm a total sugar-holic; if someone put a big gooey chocolate cake in front of me, I'd want to eat that whole cake. Yeah, if I started to eat it, I would. So I don't do it. Right. I choose to walk away from that cake, because my desire, it never goes away. It's just like alcoholism. And that's how recovery happens, too--it's choosing every day to not act on that desire. That's the cornerstone of real change--and why medicine is so ineffective. To add insult to injury, doctors fire patients when they refuse to take the prescribed medications--when they're not compliant--when patients don't "do what they've been told to do." So back to your story; you had already changed how you eat, and you still had this stroke. That's part of this healing story, that you had this family history, and then you had these incredible prayers and shamanism going on, and then there's your spirit in this--was this event you went through part of your destiny? Are you saying that I made this contract before I was born, or is it part of my genes that came through? No, I'm wondering, I'm thinking out loud--it's like our bodies give us messages, even through these catastrophic illnesses. You're getting messages, good ones--it's about trusting that inner knowing, that there's nothing better than walking the Carl Sandburg National Park trail day after day. I came down from that trail so charged, so fully charged, I just wanted to skip, I felt so full of life after what I had gone through. Then my wife, she just blew a gasket; and then finally she said, okay, you're going to do what you're gonna do. If you want to take off and walk through the old growth down there in Alabama, go do it. Do what you gotta do. So, what do you think about me getting that stroke almost two-and-a-half years after getting on that diet? I'm intrigued by that, what do you make of it? I asked my functional doctor about that, and she said, "When you have a type of illness that takes a long time to develop--that's a stroke, diabetes, that's cancer," she says, "that takes a minimum of seven-to-ten years in your body to get to that point. So if you had not made those changes, this (stroke) would have happened, and you would have probably died. But since you have gotten so much in your body cleaned out, you've recovered very quickly." I think it took probably thirty years in my life where all that was building up, but I had made enough changes, I did quickly get better. That's all possible, and that's the physical explanation. What about the bigger picture? It's here, somehow--it's in your story. I haven't looked at it until now, with disease as a form of healing. I see it more now, I'm changing to that. I see it more as a spiritual path that I'm on, that wanted me to change gears a little bit, pull out of some things, drop some of my psychological structures--they just washed away, and put me in a different place. We want you to just sit tight for six months, six years, we don't know, we'll see, we'll tell you when the time is right. That's the way I look at it, this is an opportunity for me to prepare for, whatever--if I were to die tomorrow, I would be happy about how all this happened. I have no sense that I need to go do something, but I feel like this is, maybe, a spiritual stage that I need to step through. Story is always part of an illness--even when you just get a cold, most people are run down--a cold is the only way they're going to stop "running" around--unless they use over-the-counter medications to power through, and then that just puts in more toxins, and eventually the person deals with it, or not. Everyone has free-will, whether they listen to their body messages. You're getting the message, your story seems clear--you've got the walks in the woods, and just being, you have your spiritual path. Those are gifts. And they make a good story. Let me ask you this. What is your personal philosophy about medicine and healing? There's a role for conventional medicine; they saved my life, they saved your life. I believe where medicine is headed, though, no one wants to do primary care; the spin is, oh, we need more primary care doctors. But they don't pay enough, they don't support the process, so it's just spin. When someone takes charge of their own lives, when someone starts making choices, like just giving up refined sugar--if the majority of us did that, it would change the whole country--that's what I believe in; and that kind of change is available to everybody. And that form of healing taps the inner healer that is in every person. I have a series of public service announcements. I blogged one already, that had me walking on the road, saying, did you know that a daily walk can be as effective as most antidepressants? I imagine my series of public service announcements coming on TV after each drug commercial. It's these simple things that are available to every person that can make the most difference--not the newest version of a blood pressure pill. Like a salt-water nose wash for a head cold and allergy symptoms. If we just go back to common sense--if you go to bed at the beginning of a sore throat, even for a half-day, you might not get sick. If you drink more water, guess what? You're less vulnerable to getting a bladder infection. That was part of why my community loved me, I had that kind of handout for almost anything. You were allowed to use them for awhile there, weren't you? Yes. I lived my dream while it lasted. I write a lot about this inner healer versus the outer healer, in the fourth book, Re-Creation. We all have an inner healer, and we are co-creators in our health. The outer healer is the one who needs to know about all those medications and how to interpret an EKG. They talk about creating a robot physician, and you can--of the outer healer. You can do remote medicine, even remote surgeries. But it's the inner healer that our medical system does not acknowledge, and maybe that was why I was so threatening. If somebody has a disease and they get healed through the outer healer, outer medicine, it's likely they'll get sick again; is that what you're saying? Yes. All medicine buys us time, so we can do the additional inner-healer work. Sure, we can get "fixed," but the spirit still matters. Whether we take the opportunity for deeper healing is where free-will comes in. I still have an urge to run around buying vitamins or herbs, and I've got a friend who buys all these gadgets about EMS; one emits red lights, another one, you sit on this coil and it hits you with some kind of radiation from something. Is all of that coming from part of the outer healer, or where is all that coming from? Two things; supplements and herbs can be only the outer healer, if that's all you're relying on. You know as well as anyone the value of nutritious food, that's a common-sense way of living. But do our bodies need all those supplements, is that part of the basic need for nutrition, or are they attempts to "fix" something? Or is a person's inner healer involved, do you have that inner sense that this supplement or that herb is valuable to you? That's one response. The other thing that comes to mind, is that gadgets or techniques can be used to help us detox whatever has built up in our bodies--they can provide a shortcut, is one way to say it. But then there is the question of how to create in ourselves the capacity to shed what is not useful, and how to deflect toxicity with our own strengths. Another aspect is the notion of being healed versus co-creating the healing. I used to go on shamanic journeys with drumming, and I acquired insight during them. What a shamanic healer does to someone else is like a short-cut. When I journeyed, I was co-creating directly with the healing process. When a shaman performs a soul-retrieval, he or she has more strength, has capacity to take you to a place where you can heal more quickly and deeply than on your own, and that can either be co-creating with that shaman and your own spirit, or it can be an experience only done to you. Plus, we can get pretty far on our own if a shaman isn't readily available, by co-creating more directly with our own spirit-world. I've been told by several individuals that they do not believe they have this ability; they want a guide, want to be healed by someone else. That's fine, and we all rely on one another in many ways, and receiving help can certainly lead to co-creating. In any situation, if you believe in yourself, if you begin to trust those inner knowings, more opportunities for healing occur. It comes back again to free-will; some people don't want to wake up to their own inner landscape; they just want to be fixed so they can go back to how they've always lived; they use their will to stay the same. Like with type 2 diabetes, I used to cringe when someone told me they would take more insulin in order to eat another piece of cake, rather than decrease the sugar. They were missing this opportunity to wake up. I'm glad I no longer have to face that every day. "Oh, you'd like to increase your statin dose rather than change how you eat? Okay, I can do that." That's how doctors are perceived--we are the gatekeepers to all these meds that "fix" the problem. Plus, I was fired by a few patients for not prescribing antibiotics for viral illnesses. I couldn't prescribe something that I knew would hurt them. There are parts of what you're saying that I resonate with. There are other parts that I cannot get into--I can't follow Rudolph Steiner, for example (Roger already knows that I was trained as an anthroposophic doctor); I'm a bee keeper, and I've tried to read his bee book four or five times, and I cannot get anywhere with it. I can follow the words, but I cannot understand what all that says. It's the same way with Ayurvedic medicine, Chinese medicine, the five elements, it's like, I just can't get it. I have to step back from all that, and accept some of it on faith. What I'm saying, isn't what Steiner says. As I speak, it's resonating with you, because we are both being authentic. But if I bring in Steiner or anthroposophy and things shut down, I'm not surprised. A lot of people are that way about Steiner; it's confusing, and can be intellectually exhausting. That's my Enneagram five, a coping device, trying to know and understand all that. I do love Steiner's work. I might read the same thing twelve times before getting to a place where I can grasp what he's saying. It's like poetry for me. I figure, most religions claim they are "the answer." Same with ways to heal. So they all must be true, be right, is what I've come up with. There are many ways to heal--I absorb wisdoms from all over the place, including Steiner. Are you familiar with Ken Wilber and his integral philosophy? He says everybody is right, everybody has pieces of the truth. It sounds similar to what you're saying. Yes, it does. (Pause) It's supposed to stop raining in a few hours, I'm going to go somewhere and play the fiddle for awhile. Where else do you play around here? Most recently, I played in the parking lot of the Asheville Community Yoga Center; I went to a group class for the Alexander Technique. I've been exposed to that, but it didn't do much for me. I've done a fair amount of Tai Chi, a few of those principles have been helpful. But I don't get energy. I don't receive energy, receive energetically. That's why I come up with blocks about everything. Oh, maybe that's related to the stroke. When you can't receive, it's a block. What do you mean? If I understand, is it going to free me from that? Or the stroke was because of that? Think of it as a symptom, not a cause. When you don't receive, there's a block. Think of the blockages the surgeon cleared in your neck and brain. The blood stopped flowing--the energy stopped flowing. As you learn to receive, and you're doing that--you received the message about walking in the woods and being in nature, so you do receive, that ability will grow. I think I do, but I can't sense it. Okay, maybe that's your cutting edge, the edge of your envelope that you're pushing, is you're learning to receive. I'm still not able to perceive that I receive. Right--it's just starting to develop for you. I haven't seen the fruit of that, yet. Some of it is trusting--you might not allow yourself to believe the messages you have received. Trusting ourselves, believing what we sense--that's a tough one. But you're the one telling me what you heard. You're right, it's hard for me to admit it. Well Roger, we're having an incredible encounter today, thank you. It has been, it's been dynamite for me. I did more of the talking than expected--this is the first time I've interviewed someone, I'll work on that. Anyway, I'll let you know how I use this material, maybe in a future book. What are you going to write about next? I'm playing with the theme of saints I have known--like Joan of Arc, and Julian of Norwich. Do you know about Hildegard of Bergen? A woman, I can't remember her name, wrote a book called Slow Medicine, she also wrote about medicine linked to Hildegard--that a German doctor used her writings and information to treat people. Have you come across that? I haven't, that's a great resource, thank you. That illustrates how I did what I wanted within anthroposophic medicine, and the German doctor took Hildegard's work, and with his strong inner healer, he also practiced the kind of medicine I value. I could take any form of medicine, and be a good healer with it--functional medicine, even conventional medicine, Chinese medicine--they can all bring goodness into the world. I've had a lot of TCM (traditional Chinese medicine), and same thing, I just can't receive it. Even though for five thousand years, it's worked for many other people. Your path is clearly working for you. That's true. So try to flesh out for me what a stroke might have done for me. Did I need to have that stroke to get me to the point where I can learn to receive better? Or is that just a piece of this? What do you think? I don't have any idea, I've got all these theories that I can list on the wall; none of them jump out at me at the moment. There may be a lot more gifts from that event; learning about receiving is certainly one of them. I know how challenging receiving is; I had to receive help in order to heal from my heart event. I'd much rather give; I now know receiving is as essential as giving. When people offer me help now, I know it's important to receive it. Even small gestures matter. I'm relatively elderly, and I was at a spring and had these two heavy water jugs I was carrying back to the van. And this bright young teenage fellow asked, "Ma'm, can I help you with those?" I was fine, but the gesture was so lovely, I thanked him and let him carry the jugs. Things like that. You said it very well, that you're challenged by perceiving what you receive. Maybe receiving anything--like these small gestures, will help you perceive more clearly. Oh--I'm reminded of a great exercise I use in nature. When I walk in the woods or other nature, I beam love toward all that goodness. Just beam away--and then pause, and wait to receive nature's love in return--from the trees, the rocks, wherever I am. It might take a few minutes--most of us are familiar with loving nature, and actually, nature might want to also love us back. At first when I did this, I became emotional, tearful, and sometimes that still happens--but mostly, my joy bubbles up these days. Roger smiles, and glances out the window; the rain has slowed. Thank you, Roger, for a wonderful conversation. I'm inspired to search out old growth forests after what you've described--and I will look up the medicine book about Hildegard. Happy trails to us both. As I reach for my raincoat, Roger is closing up the stove and shrugging on his jacket. We get up at the same time, leave the cozy tiny-house, and walk in the light rain, down the already saturated dirt road. Sunny with temperature in the fifties, dressed in a pair of wrist-warmers, a hand-knit red wool hat and a long sweater, I am able to comfortably play my fiddle outside.

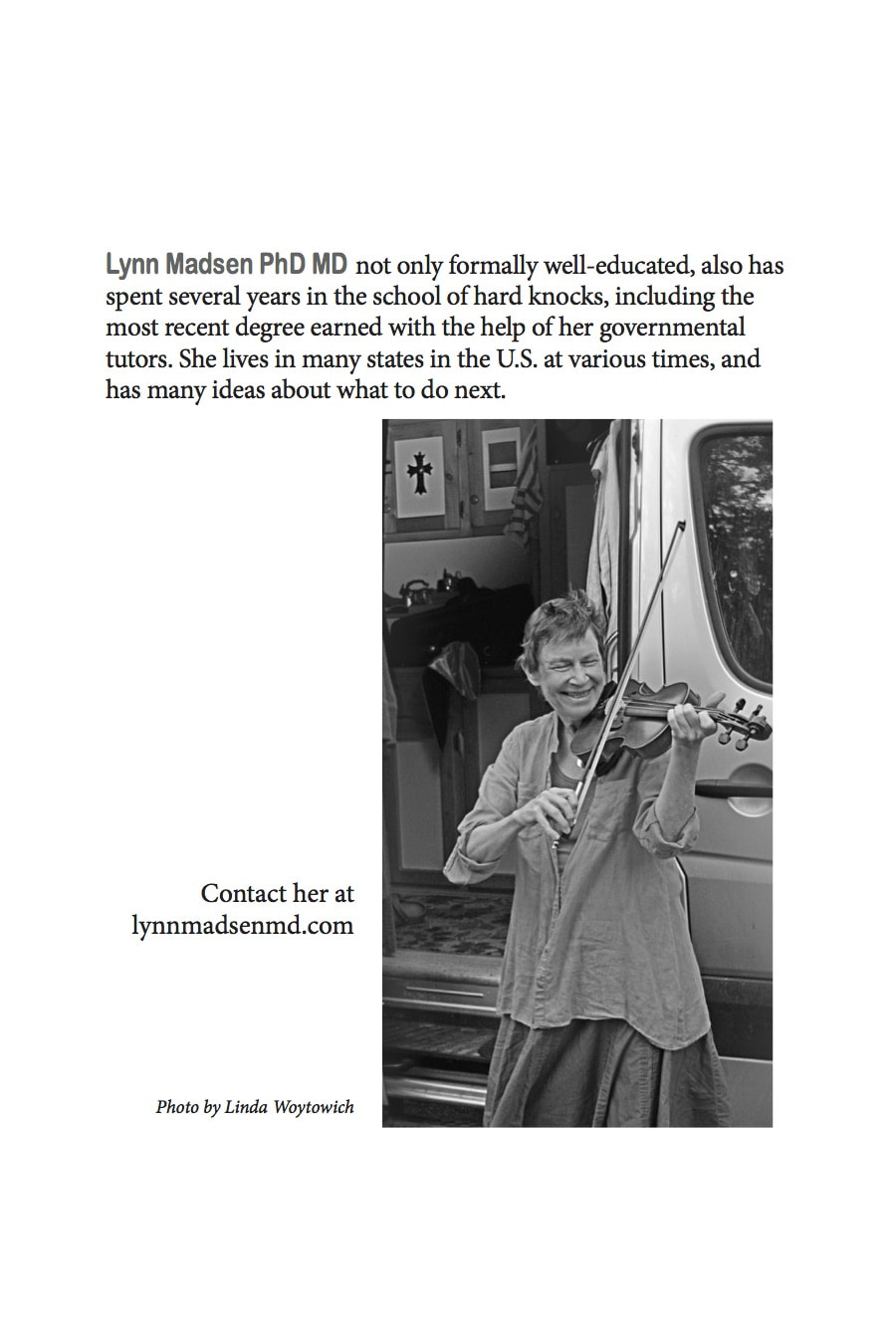

I didn’t realize how loud a fiddle is, when I bought it a year and a half ago. I used to play guitar, and one can softly play the guitar—not so easy with a fiddle. I seek out parks and roadside pullouts to play in—places where I’m anonymous, which provides a sense of freedom and lack of self-consciousness. When I first began playing, I had forests to hide in, so others could hear but not see me. Forests aren’t always an option. Now I usually stand at the side door of my van; I’ve grown more comfortable with people approaching, often interested in how I live in a van, others wanting to be near live music. Some conversations lead to how I ended up living in a van, which occasionally leads to the topic of one of my books titled, Guilty By Degree—the story of an adventure with the Feds—which leads to sometimes rummaging on the passenger seat for some of my books, and then sometimes I’m asked, “Can I buy one?” These occurrences have inspired me, on this particular day, to prop up some books on my windshield. Why not just put them out in plain sight? Already having been approached by a young man who just bought a used Sprinter and longingly looked at my hand-built interior that he could view with the side door open, a woman close to my age who just started playing the violin six months ago, and I responded, “Go home and get your violin, we could play together!” but she had lunch guests arriving soon, darn, a woman walking her dog who commented, “Sammy led me here, he wanted to be closer to the music,” now, a mature man approaches, dressed for walking with a brimmed hat and comfortable shoes. “Hi, I’m Roger.” I say my name, we shake hands, and Roger says, “Mind if I ask you about your Sprinter? I see you’ve got the Freightliner model.” “Yeah, it’s identical to the Mercedes; they’re both Daimler, the logo’s the only difference—it’s reverse snobbism on my part.” Laughing, this friendly stranger replied, “I have a Sprinter like this, but it’s one of the professionally-built models. I’m embarrassed sometimes by the Mercedes logo, too.” We chat about our mutual love of Sprinters, then he moves over to the books propped on the windshield. “If I buy only one of these, which one would you recommend?” I give him one-liners of each book’s content, and he picks out Lovely Medicine. He comments, “I had vague symptoms, mostly GI that could not be diagnosed by doctors; they just kept doing more and more tests, and then I found a functional medicine doctor who helped me completely restore my health. Then three months ago, I had a profound stroke, was unconscious for two days, was told I may live in a wheelchair. Now I’m completely recovered, and I feel better than I ever have. Like the stroke was a clearing out of something.” “You’ve chosen well, then, you’ll find yourself in Lovely Medicine.” We chat more, he hands me his card, and we wish each other a wonderful day. Roger’s story sticks with me; I want to hear more of his stroke story. Would he be open to an interview? By default, I’m becoming a journalist. Living on the road, spontaneous concerts in small parks and these chance encounters, often get me thinking about writing articles or more books—about Walmart parking lots, personal stories I hear everywhere I go about climate change, and the myriad benefits of living on the fringe of society. These impulses not yet acted on, culminate in this moment; Roger’s story could be the first of many that will nudge me out of pure memoir, and into giving voice to others’ stories. Roger is agreeable, and we meet in his nearby tiny house, his getaway place that has a wood stove the size of a shoebox. He sits next to the stove for easy stoking with more mini-logs. I sit across from him in a rocking chair, and he dives in to his story. Two-and-a-half years ago was when I resolved my gut issue—I’ve been in great health since then, consider myself in good shape; I go anywhere, and do what I want. So I wake up one morning, my wife fixes us scrambled eggs and bacon, and I’m eating the scrambled eggs, and they’re like, hard to chew; and I get into the bacon, and I can’t chew it and think, there’s really something wrong with the bacon, and I spit it out. My wife comes in and later she tells me that she saw drool coming out of my mouth, and I was tapping the table, which I didn’t realize. She asks me a question and I can’t get my words out, and I think, no problem, they’ll come out. So she gets me into the car and takes me to an urgent care place, and the doctor asks me a couple of questions and I can’t really say anything, and I keep thinking, well, they’ll come out, no big deal. Then the doctor uses the phrase, “global aphasia,” which really resonates with my wife and me—that got my attention, because my dad had a stroke; he died about ten years ago, and he lived thirteen years in a nursing home, paralyzed on one side of the body, global aphasia, couldn’t say anything—that was very traumatic for my family; he was seventy-eight, I’m sixty-six. It was terribly tragic for my family, and had to be terrible for him, living inside himself with a lot of his brain function still going. They call an ambulance and get me to the emergency room. There they inject something in me that’s supposed to clear the stroke out, and that didn’t work. So then they call up another hospital, and back in the ambulance, they get me there. I wake up two days later, and my wife was pretty distraught. The surgeon had cut open a place here (he points to his inner thigh), and goes here (pointing to his carotid artery), and there’s an obstruction and they clear that and they put a stent in, and then they go up (pointing to his skull), and there’s been blood pooling and a clot, and they clear that. And when I woke up, my wife was saying, “You’ve had a major stroke, this is a really big deal.” The surgeon had to go in twice; he told my wife I may end up in a wheelchair, and I may die. After my wife’s experience with my dad’s stroke, she was obviously very upset. But I didn’t know any of this. She told me all this and I thought they just blew it all out of proportion. I was seen by several neurologists over the next week and a half, was told, this was a very serious stroke; fortunately, your wife got you here very quickly, and I thought, oh really? I didn’t realize any of that. The occupational therapist came and put belt on me and we walked around slowly. As we were walking back, the neurologist came up to me and said, “You are a miracle.” I kept saying no big deal. I was set up to see an occupational therapist. I went through an extensive exam, and he says, “You’re okay, you don’t need anything.” So right after that I go to a speech therapist, and she says, “Well, you’ve got some issues with your grabbing words,” which we’d already noticed, and she kept me for four sessions, and then she said we were done. That pretty much sums up the medical part of the story, except that the neuorologist put me on a statin and a daily baby aspirin. I don’t like the statin and want to go off it—we’ll see. Two other parts to the story. Everybody in my family is very cognizant of my dad’s situation, they knew what this could mean. My brother lives in South Carolina, lives two and a half hours away. I’ve got a nephew in his forties who lives there; now, everybody in my family is devout southern baptist—devout; my sister’s married to a retired baptist minister, he’s got a PhD in bible theology or something like that; my wife and I left that about twenty years ago. So my nephew drove two-and-a-half hours to here, the day after the stroke happened. I was out of it, I didn’t know any of this—and he sat at my bed for ten minutes and prayed with me, then got back in his car and drove back home, and went to work. That really got to me, the amount of faith, the amount of action in faith. Another part of this is I did some work around here with a Buddhist shaman, did a long-term shaman course with her. She is now in Ireland; I found out later that one of my friends contacted her and let her know that I’d had a stroke and was in bad shape, and so she did whatever she did; I don’t know what she did. So I began to think about this Baptist approach to consciousness and God, and this shaman’s approach to consciousness. Here was the interesting part to me. I was in the intensive care for three or four days, and then they got me into a regular room. It was about ten-thirty at night; one wall was dark green; as soon as I closed my eyes, I’d go into a vision, trance, whatever you want to call it. When I opened my eyes, I’d come out of it. I close my eyes, I’m right back in it. Back and forth, back and forth. I can see some trees, some vegetation. And then I see this woman crawling around on feet and hands, it’s kind of like a low crawl, creepy looking, like a panther walking around. I’m thinking, this is quite odd. And the next thought is I might be in danger. But I think about it, and well, I don’t really feel like I’m in danger. But it’s odd, it’s pretty creepy. So this goes on for awhile, and then other animals come along, and they’re doing the same kind of thing, low crawl close to the ground. So I’m thinking, well, maybe this hospital is on Cherokee land, maybe I’m channelling the Cherokees who used to live here. I end up going to sleep, and I go through dreams that are very vivid. Two of them are that same type of thing where there’s someone slinking around close to the ground. Then I move out of that, into being in the woods. I wake up the next morning, and I bet there was a Cherokee graveyard right there. The next night, nothing happened, and I thought, no big deal. It didn’t hit me until just a week ago, that it might have been the shaman doing her process, and that was what was all around me. So then I was thinking—this is my basic religious philosophy, is that we’re all one consciousness. Let’s just say we’re all in this one consciousness, and here’s my nephew who’s praying to God who is my consciousness, your consciousness, all of our consciousness —and here is this shaman who is dealing with her consciousness through her three different worlds, dealing with animals and all that, and I’m thinking about, let’s just picture there’s a God. I don’t think there’s a God, but there’s some force, and that force is sittin’ up there, and let’s say I am this God, and I’ve got this southern baptist guy and he’s really entreating me (God), and then I’ve got this shaman woman and she’s really cranky and entreating me for you, and I’ve got both of them entreating me to do something for you. So that was my spirituality bringing all of this together and doing this healing, of whatever was going on. Then when I got out (of the hospital), I felt great. My wife was saying, I’m not going to let you out of my sight. I’m going to drive you everywhere. We’ve been married forty-six years, no big deal being together, we get along very very well, but that’s where she was coming from. I’d asked the doctor when I left the hospital, she said yeah, you can drive. My wife immediately said—you can’t drive! So for the next week and a half, she drove me everywhere, and then she was tired of it. The Carl Sandburg National Park, it’s a nice place to walk, normally I don’t go that far because it’s hard on my knees, especially back when I had the immune system issue with my intestines; but I decided I was going to go there. I didn’t tell my wife I was going—it was probably forty degrees, it was raining, it was a miserable day, and I drove there, and I had it all to myself, it was perfect. I decided maybe I would go up the trail probably a quarter of the way, and come back home. And then I thought, well, I can go a bit further, and I got half-way up. And then I end up going all the way to the top without stopping; I would stop and rest a little bit, and I went all the way up. This was a few weeks after the stroke. When I got home, she blew a gasket. I went back there every day for a week, and I kept getting better and better. I’ve just been drawn to the woods, hopefully by myself, not always. I’m leaving soon to go down to Alabama to go to this old growth forest. I’ve been doing that—walking in the woods when I can, eating it up, this place (he gestures around him to his tiny house) is a great place for me. My diet used to be totally atrocious until almost three years ago, when I did no sugar, no dairy, no grains, no legumes—and I thought when I started that, I’m going to die. Then I did it, I physically did it. My wife is a really good cook, she’s been making really good meals for me. I lost thirty-five pounds within about four months on that diet; that got my attention. I was pre-diabetic before then, and that all went away. When I left the hospital, I was down maybe three more pounds. After I got home, I lost five more pounds. Was it a spontaneous weight-loss after the event? I think I ate less, and also have been cutting back. My functional doctor told me no sugar, no xylitol, nothing like that, but you can have honey, maple syrup, coconut sugar, so I had a lot of those. But since the stroke, I’ve cut back more on those—I think that’s what happened, is cutting out more of those things. Those are the physical symptoms that I’ve gone through, and I just feel great. When the functional doctor got through with me, I felt like I was ten years younger. Now I feel five years younger than that, that’s what it’s done to me. I feel younger, more energetic, more everything, but at the same time, you’re familiar with the enneagram? I nod yes. I’m a five; we can be a pain in the butt, we really like collecting data, like to pull it all together; I seem to have lost that compulsion during the stroke. I’ve lost a lot of those traits that I would say are enneagram five, I’ve pulled back from that. I feel like the universe has told me, go sit in the corner, keep your mouth shut, and go get out in nature all you want. That’s what it feels like, that’s what I’ve been told. That’s what I’ve been doing. So those are parts of the spiritual side of all of this. I’d love to hear your response to any or all of that. What you are about to read is a chapter from the upcoming book, Re-creation: Laughing Buddha With A Fiddle.